The Future of Manufacturing Is Automating the Boring Stuff

The next frontier is not about machines. Production has already been automated to an extraordinary degree. The future lies in automating the work that has been ignored for too long.

The Future of Manufacturing Is Automating the Boring Stuff

The Future of Manufacturing Is Automating the Boring Stuff

For decades, manufacturing has poured its innovation, capital, and brainpower into automating production. Machines have been refined to run faster, more efficiently, and with greater precision than ever before. Robotics, CNC machining, additive manufacturing, and computer vision have all transformed what happens on the shop floor. Yet while production has been automated down to the second, many of the business operations that surround it remain stuck.

Processes like sourcing, purchasing, and procurement are essential to profitability, but they have not received the same attention as the machines on the floor. The irony is that while production equipment can improve throughput, it is these “back office” operations that actually determine cost, spend, and ultimately profit. By neglecting them, manufacturers are leaving massive gains on the table.

The Problem with One Size Fits All Systems

The gap is not because companies have failed to buy software. On the contrary, manufacturers have invested heavily in systems that promised to solve it all. ERP systems were supposed to unify operations into a single source of truth. Over time, these systems grew larger and more complex. Vendors pitched them as the universal answer to manufacturing’s operational challenges.

In practice, ERPs often failed to deliver on that promise. They were rigid, cumbersome, and slow to adapt to the unique workflows of each business. Over time they became outdated, either technically as the new technologies emerged or culturally as work practices shifted faster than software could evolve.

That is why email and spreadsheets have reigned supreme for decades. They are not elegant, but they are flexible. They allow manufacturers to adapt to the messy realities of custom orders, supplier variability, and market swings. They have succeeded where ERPs have failed because they give control back to the people doing the work.

But email and spreadsheets are not a strategy. They are a workaround. And today, new technology makes it possible to build tools that combine the flexibility of spreadsheets with the automation and intelligence of modern software.

To understand where we are today, it is useful to look back at how supply chain and procurement has evolved. Each generation reflects both the technology of the time and the way organizations thought about operations.

1st Generation: ERP Centric Systems (1980s-1990s)

The first wave of supply chain software was dominated by ERP giants like SAP, Oracle, JD Edwards, and Peoplesoft. These systems integrated finance, manufacturing, inventory, and procurement into one centralized platform. Their great strength was standardization for the first time, a single system could hold the entire business together.

Yet their limitations quickly became obvious. They were incredibly expensive to implement, difficult to customize, and often required companies to change their process to fit the software. Flexibility was almost nonexistent.

2nd Generation: Advanced Planning and Optimization (1990s-2000s)

In the next era, in addition to the early pioneers, companies like JDA (Blue Yonder) and Baan built tools focused on optimization and planning. These systems promised smarter forecasting, network planning, and supply-demand balancing. They used math-heavy models to simulate different scenarios and optimize decisions.

While powerful in theory, they often required pristine data to work correctly. Few manufacturers had clean enough data to truly benefit. As a result, adoption was uneven and many projects under-delivered.

3rd Generation: Cloud Based Best of Breed (2010s)

The rise of cloud computing brought a shift toward modular, subscription based software. Companies like Coupa, Kinaxis, Jaegger, and Anaplan created focused tools for spend management, procurement, and planning. These platforms were easier to implement than ERPs, cheaper to adopt, and often more user friendly.

The trade off was fragmentation. Instead of one big ERP, companies found themselves with point solutions that did not always talk to each other. Integration challenges persisted, and the promise of a truly seamless supply chain remained elusive.

4th Generation: Digital Supply Networks (late 2010s - 2020s)

In this generation, the focus shifted to visibility and connectivity. Tools like Project44, FourKites, and Interos emphasized real-time tracking of shipments, predictive analytics, and risk management. Companies like Fairmarkit enabled teams to increase visibility over spend. They created multi-enterprise networks that linked suppliers, logistics providers, and manufacturers together.

This was a step forward in collaboration and resilience, but it still left a gap in execution. Real-time visibility was valuable, but many of the core processes of procurement and sourcing were still being managed manually.

5th Generation: Autonomous and AI Driven Supply Chains (Now and Emerging)

We are now entering the fifth generation, defined by artificial intelligence and automation. Tools like Streamline for demand planning, High Radius for finance automation, Scoutbee for supplier discovery and Purchaser for RFQs. Instead of trying to do everything, these platforms go deep into specific processes and use AI to eliminate repetitive tasks.

This generation is not about one system to rule them all. It is about intelligent, specialized tools that solve real problems and integrate where needed. In other words, it is about flexibility plus automation.

Why Discrete Automation Matters

The mistake of the past was trying to build one universal system that could handle every scenario. The reality is that no two manufacturers are alike. A sourcing process at a heavy equipment company looks very different from one at an aerospace supplier. The workflows are too varied to force into a single mold.

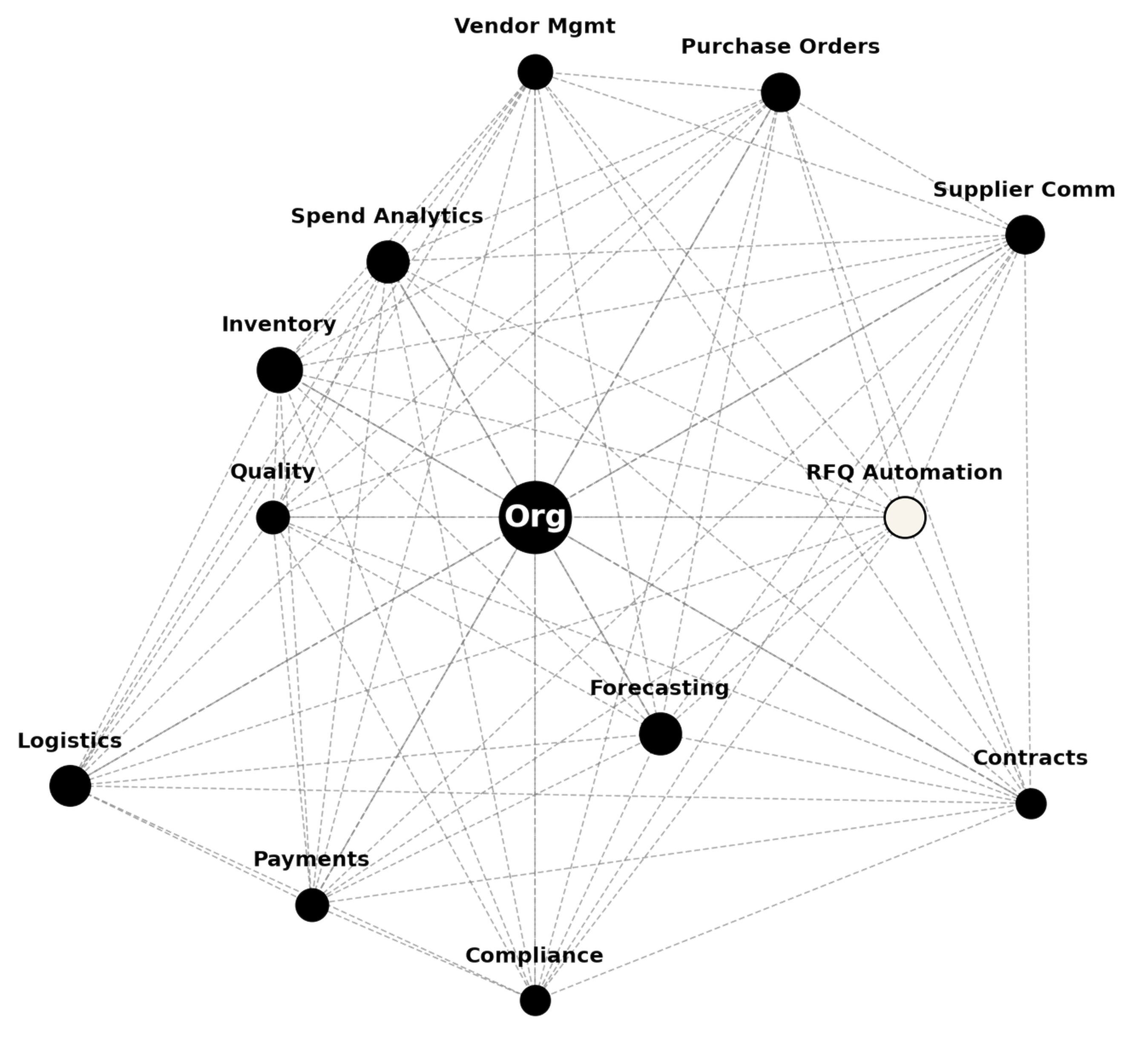

What today’s technology makes possible is a different approach. Instead of trying to solve everything all at once, companies can now automate discrete processes with surgical precision.

Take the RFQ process. It is one of the most time-consuming workflows in procurement. Quotes come in through emails, attachments, and phone calls. Someone has to copy numbers into a spreadsheet, compare options, and chase suppliers for clarifications. It is repetitive, manual, and error-prone. Automating that process removes hundreds of emails and countless copy-paste tasks. The ROI is immediate and measurable.

The same is true for supplier communications, purchase orders, and invoice matching. Each of these is a discrete process that, once automated, frees up time, reduces errors, and accelerates throughput. The cumulative effect is enormous. In many cases, the gains from automating these back-office functions are larger than what you get from another machine on the shop floor.

Organizations Should Dictate Software, Not the Other Way Around

The key principle is that software should serve the business, not force the business to serve the software. Too often, software like ERPs required companies to change their process to fit the limitations of the system. The result was frustration, workarounds, and eventual abandonment.

Modern software should do the opposite. It should fit into the unique workflows of each manufacturer, providing the flexibility to adapt while automating the tasks that add no value. Organizations should dictate the software they use, not have their processes dictated to them.

The Future of Manufacturing Operations

The next frontier is not about machines. Production has already been automated to an extraordinary degree. The future lies in automating the work that has been ignored for too long.

When you focus on automating discrete business operations, you not only reduce cost and error but also unlock new capacity. Procurement teams can run more RFQs, sourcing teams can engage more suppliers, and operations leaders can make faster, better informed decisions.

This is not about replacing people. It is about giving people better tools so they can focus on strategy rather than repetitive tasks. IT is about making procurement and sourcing as modern, data driven, and automated as possible.

The payoff is not just efficiency. It is resilience, scalability, and profitability. In an environment where supply chains are under constant stress, the companies that succeed will be those that embrace discrete automation across their entire operation.

Further Reading

Artificial intelligence is revolutionizing procurement by augmenting human capabilities, enabling professionals to focus on strategic decision-making and human-centric tasks rather than data compilation, ultimately transforming procurement into a proactive intelligence center.

RFQ intelligence elevates quoting from a transactional task to a strategic process that combines data, context, and foresight for smarter decisions.

Intelligent supply chain tools transform efficiency from a cost exercise into a people-centered strategy by connecting real-time insight with empowered decision making.

Manage complex BOMs and enforce drawing revision control.